BBC News NI weather presenter

BBC

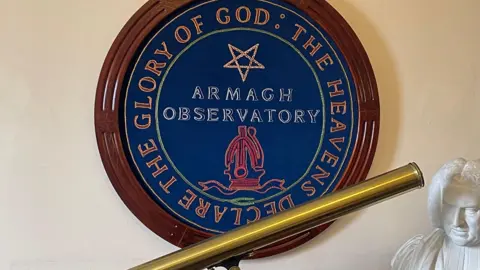

BBCArmagh Observatory is marking a very special meteorological milestone as the institute celebrates 230 years of continuous weather observation.

The unbroken tradition of handwritten data makes it the longest sequence of continuous weather information gathered anywhere in the UK and Ireland.

Events are being held at Armagh Observatory on Monday to mark the significant anniversary.

Nowadays, most weather data is gathered only by automated weather stations, but not in Armagh, where the human touch remains.

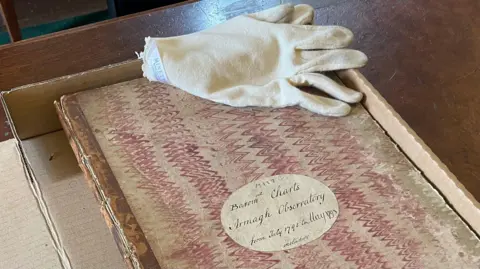

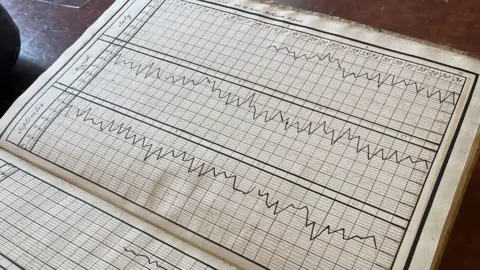

The first handwritten recording was made on the evening of 14 July 1795, when a measurement of the temperature and air pressure was recorded on a graph at the observatory that sits above the city of Armagh.

The measurement was repeated the next day and every subsequent day for the next 230 years.

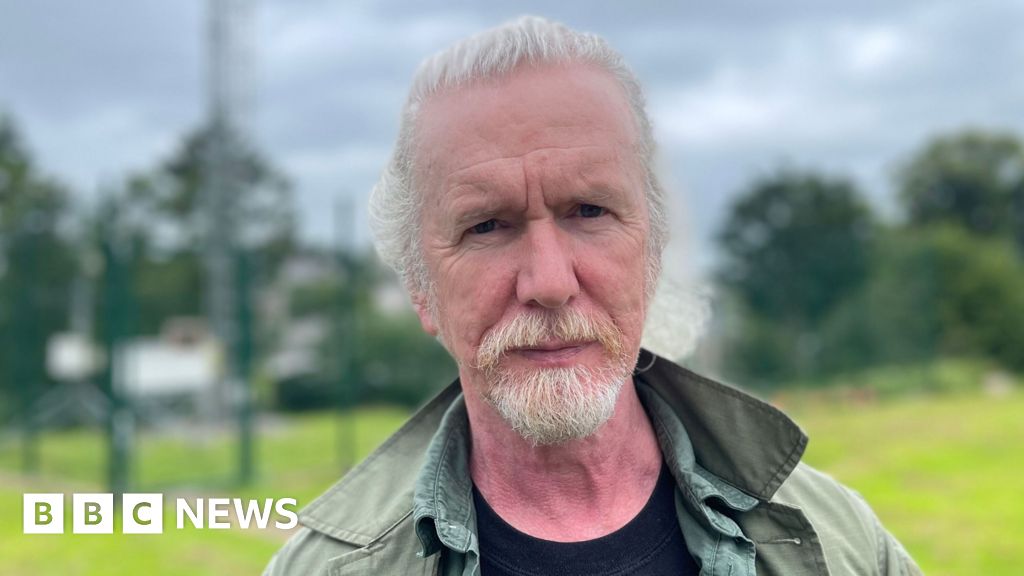

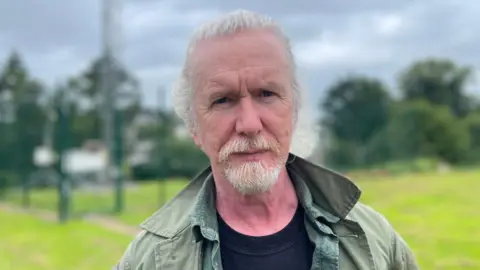

Shane Kelly is currently the principal meteorological observer at the observatory.

Since 1999, his role involves opening what is known as the Stevenson screen which holds sensitive thermometers, before noting down his readings for the day into the handwritten ledger.

His hand has entered far more lines of data than any of his 17 predecessors.

“You’re kind of ingrained in the infrastructure almost,” says Shane.

“The observatory is astronomy, it is also meteorology, and after many years I feel like I’m part of the brickwork.”

After taking readings in Armagh for 25 years, Shane says he has noticed changes in the pattern of our weather.

“The seasons aren’t quite as clearly cut as they used to be,” he explained.

“We’re kind of running into one long season with two days of snow here and a few days of sun there.”

The 230-year span of weather data in Armagh begins at the point when the science of meteorology was in its infancy.

Starting in 1795, it predates by eight years the publication of Luke Howard’s the Essay on the Modification of Clouds.

This influential book set out the naming system for clouds which, with a few modifications, is still used today.

And the observers in Armagh have left their own mark on the development of the science.

The records contain mentions of major aurora events and some of the first recorded observations of noctilucent clouds which are such a feature of clear summer nights in the north of Ireland.

The entry for the 6 January 1839, describes a “tremendous gale in the night”.

A rather understated description of a storm reported to have killed between 250 and 300 people.

In 1908, when pensions were introduced for the over 70s in Ireland, memory of Oíche na Gaoithe Móire (the Night of the Big Wind), was used as a qualifying question for people without birth certificates.

It may also have prompted the third director of the observatory – Romney Robinson – to develop a device for accurately measuring wind speed – the four cup anemometer.

Dr Rok Nežič, who is the tours and outreach officer at Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, said there were ways to measure wind speed before the four cup anemometer, “but they weren’t very accurate”.

“Robinson thought of a device that could catch wind from any direction,” said Dr Nežič, who is also a trained weather observer.

“There have only been small changes since the invention back in 1845, but we still use it today.

“From Armagh – taken around the world.”

The widow remembered as an ‘unsung hero’

The unbroken sequence of data recorded in Armagh has largely been written by men, but it was only maintained thanks to one remarkable woman.

In 1917, Theresa Hardcastle arrived in Armagh from England with her children.

Her husband Joseph had been appointed as the next director of the observatory and Theresa had arrived to oversee repairs to the house they were to share.

Before he could travel to join her, Joseph fell ill and died.

Bereaved in Armagh, Theresa continued to make and record the daily weather observations.

Jessica Moon, from the observatory and planetarium describes Theresa as the “unsung hero” of the Armagh story.

“Nobody would have expected her to do that,” she said.

“That wasn’t her role at all. She is such a key detail in this.”

Today, many of the weather observers that Shane Kelly has trained come from all over the world.

For the current observatory director Professor Michael Burton, the hands on gathering of weather data is an important part of the training process for PhD students based in Armagh.

“The process of measurement itself is the heart of science,” he said.

“But it’s not a simple process. And the process of getting hands on – of getting dirty with the data – is a key part in understanding what’s out there.

“Measuring the weather actually teaches you a lot about science… It helps you understand your data.”

That important role in training the scientists and astronomers of the future means that Armagh’s human connection to the weather of the past looks set to continue for many years to come.

Read full article at source

Stay informed about this story by subscribing to our regular Newsletter