Part of the Series

Struggle and Solidarity: Writing Toward Palestinian Liberation

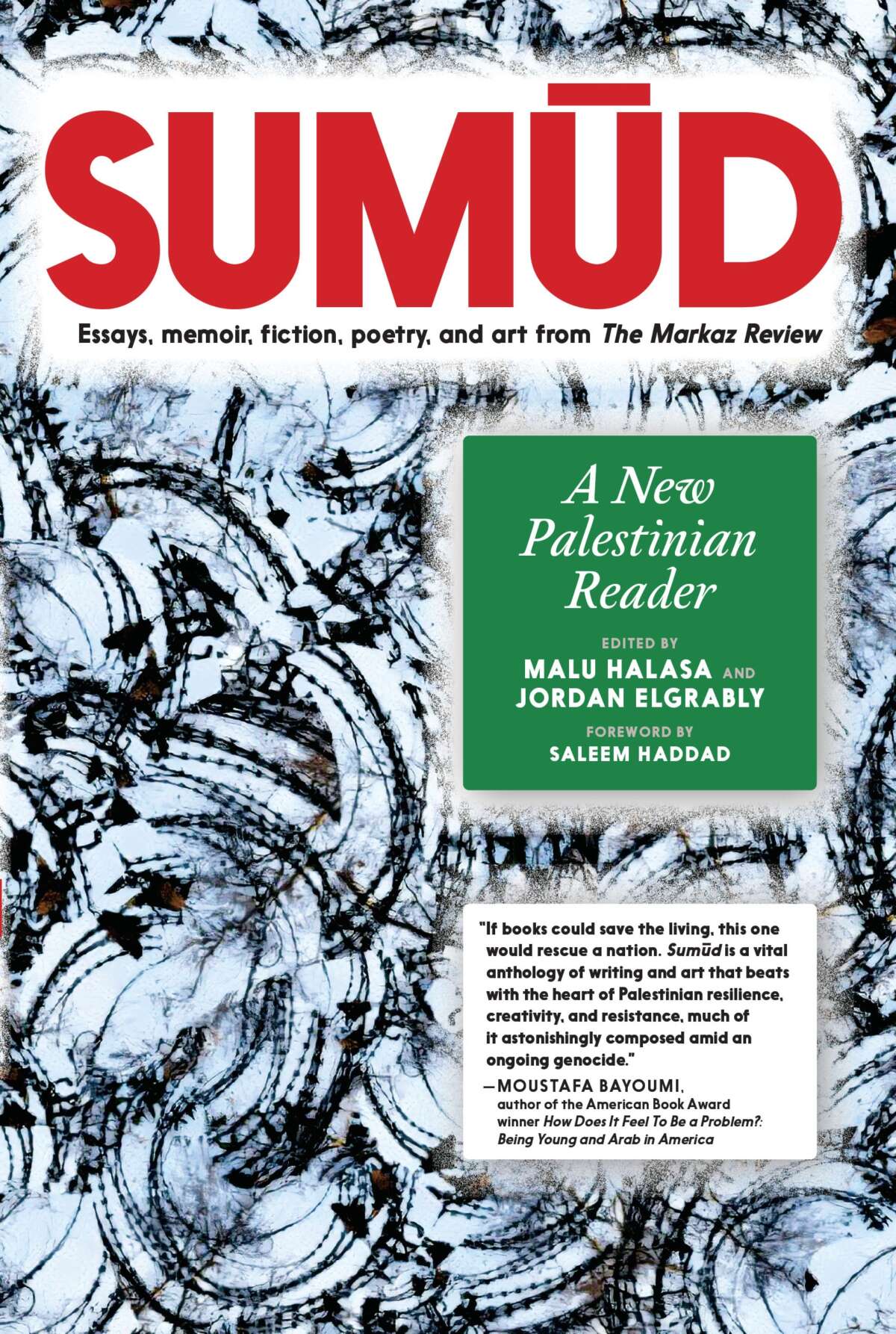

“Sumūd, the process of steadfastness, of survivance, is not just a project of survival, but also one of remembrance, record-keeping, and revitalization,” write Malu Halasa and Jordan Elgrably in the introduction to Sumūd: A New Palestinian Reader (Seven Stories Press). The world has now witnessed sumūd at its most tenacious, as Palestinians hold on to life, dignity and a centuries-old culture amid an onslaught that threatens their survival. The book’s collections include some of the most incisive political commentary, moving poetry and arresting art coming from Palestine. The intellectual and cultural richness that has been erased by decades of misrepresentation and silencing shines through on every page.

In addition to her work on Sumūd, Malu Halasa is curating the “Art of the Palestinian Poster” exhibition at the P21 Gallery in London during the city’s “Shubbak: A Window from Contemporary Arab Cultures” festival.

In this exclusive interview, the anthology’s co-editor Malu Halasa discusses the importance of art to the Palestinian struggle, how Israel has targeted Palestinian writers and artists, and how a new generation of activists is using art as part of their nonviolent resistance. The following transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Peter Handel: Your new book, Sumūd: A New Palestinian Reader, brings together essays, fiction, poetry and art primarily by Palestinian writers. What does sumūd mean and why did you choose it as the title?

Malu Halasa: As a younger generation comes to the issues of, for and about Palestine, recent discussions have been taking place about the “acceptability” of violent resistance. The argument for violence plays into Israel’s insistence that Palestinians are “terrorists” — despite a backdrop of Israeli assassination and historic targeting of moderate Palestinian voices.

The Arabic word sumūd is often translated as “steadfastness” or “standing fast.” It is, above all, nonviolent resistance.

The introduction to our anthology Sumūd begins by quoting Palestinian author and human rights lawyer Raja Shehadeh, from Ramallah: “Sumūd has ‘been practiced by every man, woman and child here struggling on his or her own to learn to cope with, and resist, the pressures of living as a member of a conquered people.’ Sumūd is both a personal and collective commitment; people determine their own lives, despite the environment of constant oppressions imposed upon them.”

In creative expression, the Palestinian people have agency. Through arts, literature and culture, Palestinian writers, artists and cultural practitioners speak for themselves, and the philosophy and lived experience of sumūd has been essential to this. So it is important for me, as someone who has written about Palestine for nearly 30 years, to champion literary, artistic, dissident and queer Palestinian voices in this “New Reader,” particularly for a generation seemingly coming to the struggles of Palestine for the first time. It is also important to show that ongoing resistance has been taking place since 1948, and that violence is not the only way that people take a stance and advance the cause of social justice in their lives.

You write, “Art was and still is perceived as a threat to the Israel authorities. In the West Bank and Gaza in the 1970s and 1980s, there were no official galleries, and artists showed their work in schools, churches, and town halls. The popularity of these exhibitions among ordinary Palestinians also drew an unexpected audience” — the Israeli military. How have Palestinian artists been persecuted and how have they managed to work despite it?

An example of sumūd is the art of the Vera Tamari, particularly a 2002 art installation called “Going for a Ride?” which she did during the Israeli invasion of Ramallah when Israeli military tanks rolled down the streets of Ramallah and crushed the parked cars in their way. (Remember, former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon enlarged the streets of Gaza City so they were wide enough for Israeli Merkavas.) Tamari took these wrecked cars off the streets of Ramallah and arranged them in an art exhibition on the edge of a school playing field. It had been so busy during the exhibition’s opening (and remember this was taking place during an Israeli incursion), the artist only had time to take two pictures of the installation. That evening, Israeli tanks came upon the installation, rolled many times over the crushed cars forward and backward, crushing them more again. Then the soldiers got out of their tanks and urinated on the installation, activities Tamari who lived nearby was able to film. In Sumūd we show the two photographs that Tamari took of her exhibition, alongside her other artwork.

During this same invasion in 2002, artist Rula Halawani went out on the streets of Ramallah, and photographed corpses of Palestinians on the roads and pavement. She printed the negatives of the photographs and entitled them “Negative Incursion.” In some circumstances the act of bearing witness is radical resistance.

In the book, there are artists who have excavated the Palestinian experience. Taysir Batniji in his “Watch Towers” black-and-white photographic series documents Israeli watchtowers. For “38 Days of Re-Collection,” Steve Sabella photographed a Palestinian home abandoned in 1948, images of which he printed on fragments of walls or plaster from Old Jerusalem homes. The cover for Sumūd was taken from Sabella’s “Metamorphosis” series, which shows barbed wire.

Poetry speaks not to the mind but the heart. Hopefully those who have hardened themselves to Palestine will hear the words of these precious, young poets.

During this war on Gaza too, artists have responded with remarkable work; for example, Hazem Harb’s charcoal drawings “Dystopia Is Not a Noun” and his abstracted “Gauze” series. There is a younger generation of artists as well: social documentary photographer Rehat Al Batniji and her portraits of Gazan fisher[folk]. Through artwork like this and more established artists such as Sliman Anis Mansour and his “Homeland” charcoal on acrylic painting showing the penning of Palestinians crossing at Erez Checkpoint to Gaza, the Sumūd anthology has the opportunity to show and discuss occupation, apartheid and colonial settlement and their effects on ordinary Palestinian lives.

Also, there is a greater story pertaining to the Palestinian flag: The periods when the Israeli authorities ban it or have allowed it to be shown; its banning on the internet and how the flag and the keffiyeh, both demonized, have been used by Palestinian artists, either outright or in the case of the flag, metaphorically through its colors. It is fascinating that the emblem of a “not yet official” state has seemingly more power than flags belonging to official nation-states. On Sumūd’s back cover is a watermelon fresco from a villa in Nazareth that was documented by the Gazan artist Hazem Harb, who writes in the book about the arrest and beating up of this father by the Israeli military in Gaza City and the urgency Harb feels as he makes art during genocide.

You include a number of poets in Sumūd. Talk about the importance of poetry in Palestinian culture.

There are many books on the politics of Palestine, and most of them, usually by political pundits or academics, concentrate on the “winners” and “losers” of the Middle East. By encountering Sumūd’s firsthand accounts of Palestinian memoir, artists’ motivations behind the artwork, and the critical analysis that challenges Israeli propaganda, readers have the opportunity to break from the usual Palestinian stereotypes that populate mainstream press and media. Poetry too provides a glimpse into the Palestinian psyche. All of us will remember the words of Refaat Alareer who allegedly received a phone call from the Israeli military saying they were going to kill him and they did — in an airstrike in 2023. Alareer had written:

If I must die

You must live

to tell my story

Poetry speaks not to the mind but the heart. Hopefully those who have hardened themselves to Palestine will hear the words of these precious, young poets.

How do you think the world’s understanding of the Palestinians’ plight has changed since Israel’s latest attack on Gaza?

I can only answer this question through my own experience as a writer and reporter on the Middle East. There has definitely been a generational change in terms of attitude toward Palestine. Nineteen-seventy was one of the first times I went to Jordan-Syria-Lebanon to report a big story. This was during the Lebanese civil war, and I had been working at Rolling Stone magazine. I returned with an interview with Palestine Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat, which had been difficult to get in war-torn Beirut. Absolutely no one was interested.

I spent the next 10 years working as a music journalist. By then I had moved from New York and was covering rap in Britain. It was the hundreds of hours I spent interviewing Public Enemy and writing on Black American history that I started thinking about my own family culture, and the stories I wanted to tell from my experience and background. The Jordanian side of the family has strong ties to the Palestinian struggle, with members of our extended family in the West Bank. Family stories eventually became the basis for my debut novel Mother of All Pigs, a fictional account of my uncle who had raised pigs in the mountains of Jordan. But again, I had tried to publish a draft of the novel in the early 1990s, and nobody was interested. Time has changed all of that.

In my own writing about Palestine, I remember I had become obsessed with water as a civil rights issue for Palestinians. After traveling and reporting in the West Bank, Gaza Strip and Israel, I wrote a feature-length piece about water shortages and permaculture in Palestine. Essentially to make the desert green, the Israelis draw precious water from underground aquifers beneath the West Bank, grow avocados and herbs, which they sell through major U.K. supermarkets to essentially water-rich nations.

However, that year, 1998, there had been a drought in Britain. Despite the fact that a mainstream newspaper had contributed to the finances of my trip, once it rained in Britain, the newspaper editor no longer wanted the story. It was these kinds of scenarios that someone like me with an interest in reporting from and about the Middle East for the mainstream media regularly encountered. This is how it was, and in many ways this situation hasn’t changed. We only hear or read about the region when it’s at war.

So against this backdrop of indifference The Markaz Review has emerged as an important publication. In the mid-2000s, when I was the managing editor for the book imprint belonging to a Dutch cultural fund, I came to understand that cultural expression can be a platform for authentic, non-elitist voices from the Global South. I then started co-editing and producing wide-ranging anthologies, initially featuring new writing and images from Beirut and Tehran, and then later from the Syrian revolution and more recently the women’s protests in Iran. When the war on Gaza started in 2023, I started talking to Markaz’s Editor-in-Chief Jordan Elgrably about producing a “Palestinian Reader,” for all the reasons I’ve discussed above.

In my decades of writing about the Middle East, whether through the prisms of politics or culture, I never thought I would see this groundswell support for the Palestinian cause in my lifetime. The Israelis remain adept at controlling the narrative and shutting down criticism of their brutal occupation and disenfranchisement of the Palestinian people. Today, we’re seeing the effects of right-wing, pro-Israeli groups on the Trump administration: the arrest and threatened deportation of pro-Palestinian students from the U.S. and the intimidation of anti-Zionist Jewish voices.

The one thing Israel and the U.S. administration cannot control are the stories of genocide and starvation that continue to come out of Gaza. All over the world, shocking images appear in real time on people’s phones. These are the truths that cannot be hidden, ignored or denied.

Help Truthout resist the new McCarthyism

The Trump administration is cracking down on political dissent. Under pressure from an array of McCarthy-style tactics, academics, activists and nonprofits face significant threats for speaking out or organizing in resistance.

Truthout is appealing for your support to weather this storm of censorship. We fell short of our goals in our recent fundraiser, and we must ask for your help. Will you make a one-time or monthly donation?

As independent media with no corporate backing or billionaire ownership, Truthout is uniquely able to push back against the right-wing narrative and expose the shocking extent of political repression under the new McCarthyism. We’re committed to doing this work, but we’re also deeply vulnerable to Trump’s attacks.

Your support will help us continue our nonprofit movement journalism in the face of right-wing authoritarianism. Please make a tax-deductible donation today.

Read full article at source

Stay informed about this story by subscribing to our regular Newsletter