BBC News

BBC/Lee Durant

BBC/Lee DurantDays after a 7.7-magnitude earthquake shook Myanmar at the end of March, killing at least 3,700 people, the country’s ruling junta agreed to a halt in its devastating military campaign.

It then violated that ceasefire, again and again.

I went inside rebel-held territory in the eastern Karenni state for 10 days from mid-April. I witnessed daily violations by the junta, including rocket and mortar attacks which killed and injured civilians and resistance fighters.

One of those was Khala, a 45-year-old father killed in a strike by military warplanes, in a place his wife Mala said should have been safe.

When the ceasefire was announced, on 2 April, Mala and Khala sensed an opportunity to return to their home for the first time in years.

With their four-year-old child, they headed from the camp where they’d taken refuge to their village, Pekin Coco. They found it abandoned, with buildings shattered from drawn-out fighting. Almost everyone there had moved to farmland further away from the junta’s weapons.

But as the young family was about to leave Pekin Coco again, their car loaded with their possessions, the shelling started.

“We were all at the front of the house. Then, shells landed near us. We hid at the back of the house. But he [Khala] stayed where he was,” said Mala. “The artillery shell landed and exploded near him. He died in the place where he thought he was safe.

“He was a good man,” she said and began to cry.

Later that afternoon, the junta’s warplanes attacked a house on the same street, killing four more men.

“I hate them,” Mala said. “They always attack people without reason. I don’t feel safe here. Jet fighters are flying over the sky often but there is no place to hide.”

Mala is 31 and seven months pregnant. When we spoke she was back in a displaced people’s camp, grieving. Her son Zoe, missing his father, wouldn’t leave her side.

BBC/Lee Durant

BBC/Lee Durant BBC/Lee Durant

BBC/Lee DurantBefore the earthquake, Myanmar was in the midst of a nationwide civil war.

After decades of military rule and brutal repression, ethnic groups, along with a new army of young insurgents, brought the dictatorship to crisis point. As much as two-thirds of the country has fallen to the resistance.

Tens of thousands of people have been killed, including many children, since the military seized power in a coup in 2021. The UN says the earthquake has pushed a further two million people into need, some 2.5 million were already displaced before the quake.

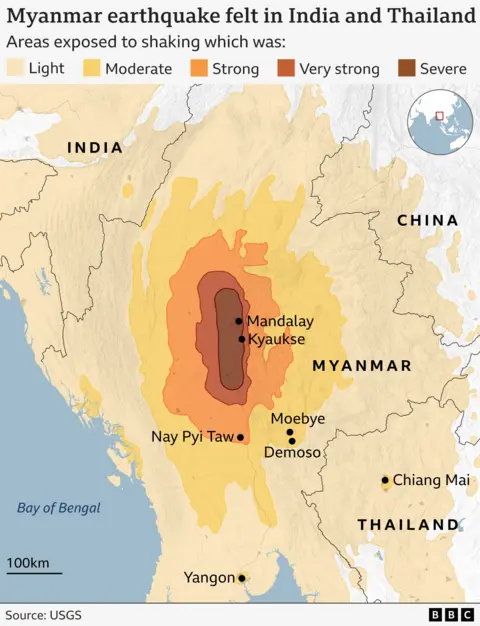

Karenni, or Kayah, state is far from the earthquake’s epicentre. Its remoteness is both a blessing and a curse. Its thick jungle provides cover for those who oppose military rule, but it is difficult to get around, the roads are poor and main highways remain in range of the army’s guns. Most of the state is now controlled by rebel and armed ethnic groups.

On 28 March when the quake hit, there were no reported deaths in Karenni – but the hospitals still filled quickly with people suffering spinal and crush injuries.

A 30m (100ft) sinkhole had appeared in the forests around the town of Demoso. Locals who heard the ground open up thought it was another air strike. For many weeks, the sinkhole continued to expand with the aftershocks.

BBC/Lee Durant

BBC/Lee DurantThe UN noted that the Myanmar military continued operations after the earthquake and beyond the ceasefire, and called for them to end. The State Administration Council, the ruling junta, has not commented on the alleged violations but has claimed that it was attacked by resistance groups. During the ceasefire all sides in the conflict have reserved the right to respond if attacked.

During my 10 days in Mobeye, Karenni, I witnessed daily attacks by the junta.

I met Stefano there, a 23-year-old fighting the military dictatorship with the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force (KNDF).

He leads a platoon of young fighters who have set up trenches around the base.

From a dugout just 100m (330ft) from the junta’s positions, he explained the army had continued attacks “using all means” during the ceasefire – soldiers on the ground, drones and jets.

“They usually attack with drones and heavy artillery on this side. When it rains, they advance by taking advantage of the weather.”

He called the ceasefire a “joke”.

“We did not believe the military council from the beginning. We don’t believe it now, and we won’t believe it in the future.”

BBC/Lee Durant

BBC/Lee Durant BBC/Lee Durant

BBC/Lee DurantThe day after we spoke, the military launched a full-scale assault with heavy weapons and men, attacking rebel lines. As we made our way to the front lines, small-arms fire could be heard nearby, along with mortar strikes. The ground was pitted with fresh hits from armed drones.

Nearby lay the corpse of a junta fighter who had tried to breach the rebel positions. The resistance forces say they have suspended all offensive activities during the ceasefire, but they have said they will respond if attacked. Yi Shui, the commander of another resistance group, the Karenni National Army, showed me pictures on his phone. “When we saw them, we shot them. One of them got hit” and another ran away, he said.

And again, the military wasn’t just targeting the resistance forces. Its rockets hit farmland beyond, killing a 60-year-old woman. We arrived at fields where four rockets had landed, children were playing with the bent metal and shrapnel from the strikes.

The injured were taken to local hospitals, which are hidden deep in the jungle to avoid air strikes from junta warplanes.

In one, a young fighter was being treated in a wooden ward with a dirt floor. He had a shrapnel wound to his shoulder and was losing a lot of blood.

The doctor in charge, 32-year-old Thi Ha Tun, said he’d treated around a dozen patients for war-related injuries since the ceasefire was declared. Two of the patients, resistance fighters, died.

BBC/Lee Durant

BBC/Lee DurantHe dismissed what he called the junta’s lies. “They only care about their own interests,” he said. “They will only care about their own organisation. They will not care about the rest of this country, their own generation, the youth, the children, the elderly, anything.”

The only solution is to keep fighting, he said.

High on a hilltop in the rebel-controlled areas is the church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The earthquake brought down the church steeple and part of the roof. The bell from Rome now sits in a temporary cradle. Repairs have been made, but the church will probably need to be rebuilt.

They are still feeling the aftershocks here weeks later.

But for Father Philip, the local priest, the greatest threat to his congregation, many of whom are the war displaced, comes from above, not below.

“No place is safe. When we have jet fighters flying in the sky… you never know what will come falling from the sky.”

Back at the Mobeye front, Stefano and his men pass the hours between attacks, cleaning their weapons and singing songs. “I can hear the people’s prayers, cries, and cries. We will overthrow the dictatorship,” they sing in unison. They say the only ceasefire they will trust will come with the junta’s defeat.

The truce will finish at the end of the month, but for most of the people here, it’s as if it never existed at all.

Read full article at source

Stay informed about this story by subscribing to our regular Newsletter