Disabled people hold immense expertise in navigating both chronic illnesses and moments of crisis. And yet, despite all the public reflections on “lessons learned” at the five-year anniversary of the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic — from which hundreds of people in the U.S. are still dying each week — disabled people find themselves under increasing attack by the Trump administration.

Government rhetoric about disability, from White House policy memoranda to social media posts, dehumanizes disabled communities, characterizing people as “burdens” and “threats” to the nation, and prompting new fears about institutionalization. Perhaps most urgently, Medicaid, Social Security and Section 504 accommodations — and possibly even the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act — are at serious risk of defunding and dismantling, among other fragile elements of the social safety net.

Additionally, noted vaccine denier Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has been installed as secretary of Health and Human Services, abruptly changing vaccine recommendations (including no longer recommending COVID-19 vaccines for children or pregnant people, and other policies that could limit vaccine access), and threatening the likelihood of new global infectious disease outbreaks. Elon Musk’s “Department of Government Efficiency” has attempted to dismantle entire agencies like USAID, laid off experts at federal agencies, and removed crucial data and agency websites. And federal grant programs, including the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation (NSF), have been slashed, with a prohibition on terms related to diversity, equity and inclusion — including “disability” and “accessibility” — imposed on remaining funds, cutting urgent funding for infectious disease and public health research (including social science research, like that for this book, which was funded by the NSF).

These are only the tip of the iceberg: Disabled people, their families, allies and service providers are particularly affected by these attacks. (Plus, it should be noted, Democrats are not off the hook, as many activists have critiqued premature rollbacks of COVID-19 resources, as well as recent attempts by politicians like New York Gov. Kathy Hochul to implement a mask ban.) And, of course, disabled people are also uniquely affected by other inhumane policies, including attacks on migrants and trans people, unpredictable tariffs and foreign policy.

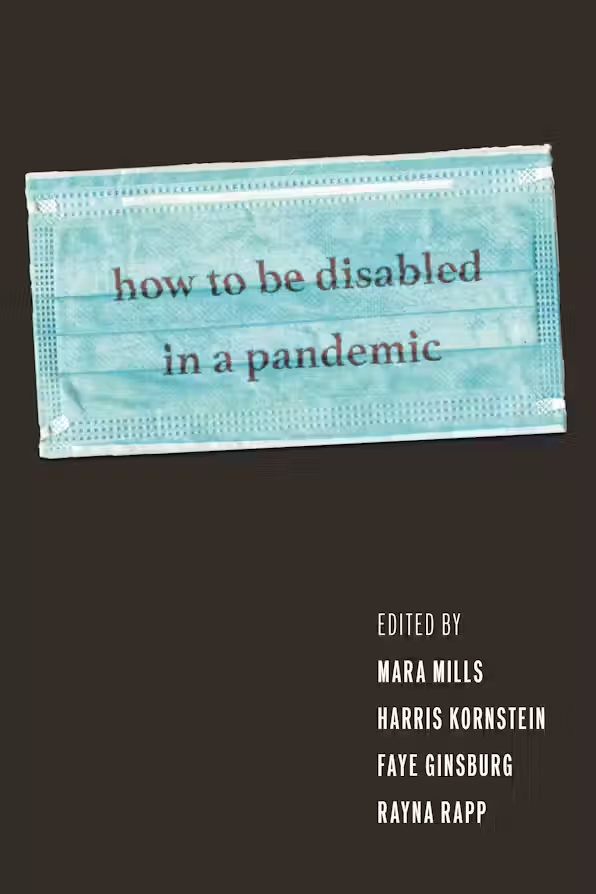

In this context, while the facts on the ground documented in How to Be Disabled in a Pandemic about the earliest days of COVID-19 may have shifted, the book’s key takeaways — especially that pandemic social movements must be rooted in disability justice — are more timely than ever.

“Disability Is an Ingenious Way to Live”

A dialectic of risk and resistance has played out in many different arenas of public life and discourse during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially as disabled people contest institutions and policies that are both overtly and more insidiously ableist. Among those who survived, among those with means, amid networks of mutual support and care, and among disabled artists, many demonstrated time and again that, in the words of Neil Marcus, “disability is an ingenious way to live.” In documenting moments of struggle, insight and improvisation, however, we resist the impulse to romanticize precarity.

When Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky, a top public health leader in the U.S., apparently claimed that it was “encouraging news” that the majority of COVID-19 deaths were among those “who were unwell to begin with,” it prompted massive protest. #MyDisabledLifeIsWorthy, a hashtag launched by Imani Barbarin in January 2022, directly countered Walensky’s comments and reasserted the value of disabled life. #MyDisabledLifeIsWorthy sparked wide-ranging conversations about neo-eugenics in government policies, and within a week, on January 14, Walensky met remotely with a group of disability activists to apologize for her comment, promising regular meetings going forward. Despite this seeming win, these regular meetings did not happen, and biases in public health policy effectively became self-fulfilling prophecies, requiring an ongoing, iterative series of protests.

Ableist sentiments were further translated into a range of policies that directly threatened many disabled people’s health and ability to participate in public life. One major form of injustice that emerged in spring 2020 centered around medical triaging and the rationing of lifesaving treatments that deprioritized or outright denied care to people with a variety of disabilities, judging that their lives were “too expensive” or “lost causes.” For example, a 2021 report by the National Council on Disability found that “people with intellectual or developmental disabilities, and medically fragile and technology dependent individuals, faced a high risk of being triaged out of COVID-19 treatment when hospital beds, supplies, and personnel were scarce.” In the earliest days of the pandemic, access to ventilators was notably limited, leading to state- and hospital-based rationing proposals for withholding or withdrawing lifesaving equipment from certain groups of disabled people.

Similarly, when vaccines became available to select groups, many disabled people who were at increased risk were nonetheless not included on the initial lists for priority access in New York State, as only a limited number of “comorbidities” were considered. Unsurprisingly, people whose conditions were not listed protested their longer waits, while activists in other states contested policies that failed to recognize disabled people at all. The pandemic underscored the endemic ableism of health care allocation and the stark irony that those who need care the most often cannot access or afford it in the highly stratified privatized U.S. health system. At the same time, as supply chains faltered at different moments, disabled authors shared their unsentimental expertise about how to self-ration when unable to access or afford drugs and medical supplies, offering advice about things like sharing insulin and other hormones or crowdsourcing catheters.

Organizing Against Ableism During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Disabled people have organized creatively against any number of structural and legal barriers to health care, education and information, transforming architecture, city streets and digital media in the process. During the pandemic, activists were pleased to see expanded options for telemedicine, for which they had long been advocating (and which was temporarily expanded by Medicare and most private insurance under pandemic emergency orders). Yet they also expressed frustration at seeing “ableds accommodating themselves with the accessibility … disabled people fight for every day,” exemplified by the hashtag #AccessibilityForAbleds. The pandemic revealed just how easy it could be to provide certain accommodations — such as remote access to work, school and therapy — that disabled and chronically ill people had been demanding, unsuccessfully, for years.

With the prioritization of urgent COVID-19-related care, necessary in-person appointments were frequently delayed or canceled as medical resources were reconfigured or facilities deemed too risky. Moreover, as care professionals, especially at-home care workers, became ill, refused vaccines or left the profession, many disabled people found it increasingly difficult to receive basic services; the National Council on Disability notes that this left “some at risk of losing their independence or being institutionalized.”

This complex situation highlights the overlapping precarities of the pandemic: The majority of nursing assistants and home care and direct care workers are women of color, who earn less than white men and who also experienced higher rates of death than average from COVID-19. Under these seemingly impossible conditions, disabled people and their families demonstrated “ingenuity and creativity … to make home accessible” using a range of improvised hacks. Laura Mauldin documents these in her research on “disability at home,” accompanied by a photo website where people share images and stories of how they have created access on their own.

Many blind and Deaf people also faced specific barriers to information and treatment for COVID-19 as a result of inaccessible websites, the limited availability of captioning and interpreters, or a lack of materials in Braille and other accessible formats. For instance, many forms of COVID testing have been inaccessible to blind people, from drive-through testing sites to home tests that rely on visual instructions and displays. Some apps, such as Be My Eyes, founded by the visually impaired inventor Hans Jørgen Wiberg, have allowed blind people to video call sighted people for assistance with visual tasks such as reading rapid test results. Frustrated by the slowness and potential COVID exposure of in-person testing sites, Mark Riccobono, president of the National Federation of the Blind (NFB), wrote to President Biden on January 3, 2022, on behalf of the thousands of NFB members to demand that the free COVID tests provided by the federal government include versions accessible to blind people. He followed up with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) commissioner shortly after, requesting that kit instructions on the FDA site be posted as accessible PDFs. In response, in June, the U.S. Postal Service temporarily provided what it called “more-accessible” COVID tests, although these versions still required a smartphone and navigation of the Ellume app (not created for blind people) to hear audio instructions and results.

Cross-Disability Solidarity and Aid

As with any dialectic, experiences of disability during the pandemic were hardly defined strictly by either vulnerability or creativity; instead, disabled communities often directly wrestled with this sort of binary thinking, challenging each other to embrace complexity. The pandemic also raised numerous instances of what disability scholars describe as “access friction,” in which actions that increase access for some may limit or hinder access for others.

For example, while masking in public spaces has been a key mitigation strategy, particularly important for immunocompromised people, most masks are opaque and muffle sound, which can pose a barrier for deaf and hard-of-hearing people, especially when reading lips. Similarly, while options for remote work, schooling and socializing provided welcome enhancements for those who had long been advocating for such access strategies, for many disabled students — among other groups — remote participation both exacerbated existing inequities and instigated new ones.

While the disability dialectic suggests resistance and creative response by those who are immediately experiencing conditions of inequality and abandonment, many of the chapters in How to Be Disabled in a Pandemic foreground instead cross-disability aid and illness coalitions, what the late disability rights activist Stacey Park Milbern has named “crip doulaing.” In conversation with Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha shortly before the start of the pandemic, Milbern underscored the urgency of “disability doulaship”:

I see a lot of disabled people of color doing a ton of work in supporting people rebirthing themselves as disabled (or more disabled). This looks like a lot of things—maybe learning how to get medicine, drive a wheelchair, hire attendants, change a diet, date, have sex, make requests, code switch, live with an intellectual disability, go off meds, etc. etc…. I feel like society not having language to describe this transition or the support it requires speaks to the ableism and isolation people with disabilities face in our lives.… Without crip intervention, we are frequently left alone to figure out how to be in our bodyminds and in this ableist world.

In parallel, the What Would an HIV Doula Do? Collective members invoked the history and importance of illness doulas in their zine “What Does a COVID-19 Doula Do?“

Networks like Sick in Quarters (SiQ), launched in 2020, hosted smaller community-building workshops online, including virtual “right to mourn” spaces and listening session “hideaways.” SiQ describes its online meetups as a “container for collective mourning, the kind of pain and alienation that was already familiar to disabled and immunocompromised lives.” These projects thus highlight the importance of grief not only as an individual effect but also as a collective and political process in responding to the pandemic and forging intersectional solidarities.

How to Be Disabled in a Pandemic is available wherever books are sold, and in a free, downloadable, open-access e-book format via NYU Press.

Help Truthout resist the new McCarthyism

The Trump administration is cracking down on political dissent. Under pressure from an array of McCarthy-style tactics, academics, activists and nonprofits face significant threats for speaking out or organizing in resistance.

Truthout is appealing for your support to weather this storm of censorship. We fell short of our goals in our recent fundraiser, and we must ask for your help. Will you make a one-time or monthly donation?

As independent media with no corporate backing or billionaire ownership, Truthout is uniquely able to push back against the right-wing narrative and expose the shocking extent of political repression under the new McCarthyism. We’re committed to doing this work, but we’re also deeply vulnerable to Trump’s attacks.

Your support will help us continue our nonprofit movement journalism in the face of right-wing authoritarianism. Please make a tax-deductible donation today.

Read full article at source

Stay informed about this story by subscribing to our regular Newsletter