Getty Images

Getty ImagesSoon after Donald Trump returned to the White House in January, he began raising tariffs, brushing off warnings from economists and businesses about the risks of economic damage.

He started with Mexico, Canada and China, then targeted steel, aluminium and cars, and finally in April, on what he called “Liberation Day”, unleashed a blitz of new taxes on goods from countries around the world.

The plans hit trade and roiled financial markets. But as worries mounted, Trump quickly suspended his most aggressive plans to allow for 90 days of talks.

As that 9 July deadline approaches and the president crafts his approach, he will have one eye on the US economy.

So what has the impact really been?

The stock market – a wash

Trump’s plans included tariffs of 20% on goods from the European Union, punishing tariffs on items from China of 145%, and a 46% levy on imports from Vietnam, though on Wednesday he announced a deal that will see the US charge tariffs of 20% on Vietnam.

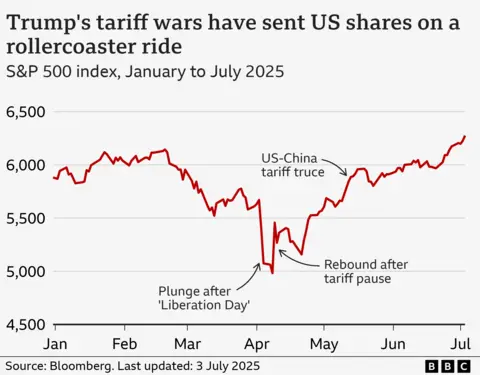

The US stock market suffered the most immediate hit, starting to slide in February and finally tanking in April after Trump unveiled the full scope of his plans, on so-called “Liberation Day”.

The S&P 500, which tracks 500 of the biggest companies in the US, dropped about 12% over the course of a week.

But shares bounced back after Trump rolled back his plans, abandoning steep tariffs in favour of a more easily swallowed 10% rate instead.

Now, the S&P 500 index is up about 6% for the year. In the UK and Europe, shares have also rebounded.

But shares of tariff-vulnerable firms, such as retailers and car companies are still hurting – and there is more risk ahead, as the talks deadline approaches.

The White House has left its options open, saying both that the deadline is “not critical” and that the president may simply present other countries “with a deal” on that date.

Liz Ann Sonders, chief investment strategist at Charles Schwab, said the rebound suggested “a lot of complacency” among investors, who risk being spooked again should Trump revive higher tariffs than they expect.

Trade – at a crossroads

NurPhoto/Getty Images

NurPhoto/Getty ImagesTrump’s tariffs precipitated a rush of goods to the US in the early part of the year, followed by a sharp drop in April and May.

But zoom out a bit, and US goods imports in the first five months of the year were up 17% compared with the same period last year.

What happens in the months ahead will depend on whether Trump extends his pause – or revives his more aggressive plans, said Ben Hackett of Hackett Associates, which tracks port traffic for the National Retail Federation.

“At this point it’s anybody’s guess,” Mr Hackett said, noting that for now the situation was “in a holding pattern”.

“If the tariff freeze disappears and the high tariffs are reimposed then almost certainly we’re going to have a short recession,” he added.

Prices – too soon to say

Bloomberg/Getty

Bloomberg/GettyIn the US, imported goods are estimated to account for only about 11% of consumer spending.

Trump and his allies have argued that fears that tariffs – which, on average, are now roughly six times higher than they were at the start of the year – will drive up the cost of living for Americans are overblown.

They have pointed in part to recent inflation data, which showed consumer prices stepping up just 0.1% from April to May.

But certain items, such as toys, saw far bigger jumps and many goods facing higher duties have not yet made it to shelves.

Firms, especially those cushioned by strong profits, could opt to pass the increases on gradually, rather than alienate customers with an abrupt jump.

Despite pressure from the president to “eat the tariffs”, economists still widely expect customers to pay for them eventually.

“If you’re not digging more into the data you would think, ‘nothing to see here’ from an inflation standpoint,” says Ms Sonders. “But it’s premature at this point to hang the victory banner.”

Consumer spending – slowing

Economic sentiment in the US started falling earlier this year, as Trump began to set out his tariff plans.

But political views play a big role in shaping opinions on the economy, so whether the worries would actually lead households to clamp down on spending over the long term remained a matter of debate.

We are now starting to see signs of pullback: retail sales dropped 0.9% from April to May, the second month in a row of decline. It was the first back-to-back fall since the end of 2023.

Overall consumer spending grew at the slowest rate since 2020 in the first three months of the year, and slipped unexpectedly in May, the most recent month for which data is available.

But while growth is still expected to slow significantly compared with last year, most analysts say the economy should be able to escape a recession – so long as the job market continues to hold up.

Though layoff notices have been pacing higher, for now, unemployment remains low, at 4.2%. Job creation last month continued at a pace similar to the average over the last 12 months.

“We’re sort of in this stall mode right now in the economy, a kind of wait-and-see mode, that is driven by pretty grave uncertainty and the instability in policy,” Ms Sonders said, noting that many firms were responding with a self-imposed “time-out” on hiring and investment.

The economy is unlikely to escape unscathed, she warned.

“It’s hard to lay out a scenario of a pickup in growth from here,” she said. “The question is more, will it just be a softening of the economy or a bigger slide.”

Read full article at source

Stay informed about this story by subscribing to our regular Newsletter